Channel Dash – The Bravest of the Brave

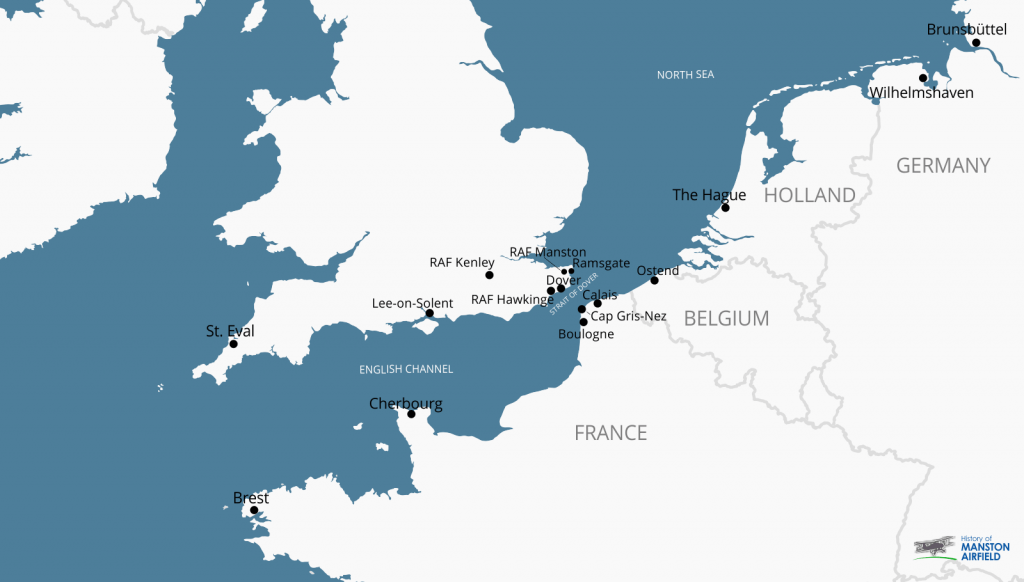

12th February 2023 marked the 81st anniversary of the Channel Dash in 1942. Three of Germany’s largest battleships ran the gauntlet of the Dover Strait from their location at Brest back to Germany where Hitler believed they would be essential for the defence of Norway. The German operation was known as “Operation Cerberus” (Unternehmen Zerberus).

In response, the Royal Navy and RAF as part of the pre-planned “Operation Fuller” – a series of combined attacks, would attempt to destroy or disable the mighty warships.

“Operation Cerberus – The Channel Dash” by Philip E. West – Reproduced with permission from SWA Fine Art Publishers. Here we see the Swordfish flown by Sub. Lt. Kingsmill and Sub. Lt. Samples with PO Bunce in the rear, fighting for their lives with his machine gun.

As part of that operation, slow, aged and fabric covered Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers of the Fleet Air Arm, would be ordered to attack the ships from the base at RAF Manston. Without the majority of their fighter cover, the airmen knew that their chances of success and survival were slim, but pressed on regardless. All six aircraft were shot to pieces by the intense German defences, including up to date Luftwaffe fighter cover, with only five of the 18 aircrew surviving.

The Battleships

The three battleships at Brest were Sharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen.

Scharnhorst was 234.9 metres long, with 11 inch guns amongst her armoury that had an effective range of 10 miles. Her displacement was over 38,000 tons when fully loaded. She could travel at the 31 knots (36 mph) and had a maximum range of 8,200 miles. She had taken part in many battles including the sinking of the British aircraft carrier HMS Glorious on 8 June 1940, hitting her from well over 14 miles away – one of the longest naval gunfire hits ever recorded. She had been taken to Brest for safety and for remedial work to her faulty boilers. She had a compliment of 56 officers and 1,613 enlisted sailors.

German battleship Scharnhorst. Bundesarchiv – CC BY-SA 3.0 de

Gneisnau was the sister ship to Scharnhorst and they often operated together to attack the Atlantic Convoys, but were themselves often vulnerable to attack from the larger ships of the Royal Navy. After the last successful raid on convoys, she too docked at Brest for refuelling and repairs.

Schlachtschiff “Gneisenau” CC BY-SA 3.0 de

Prinz Eugen was smaller than the other two massive ships, as a heavy cruiser of 18,710 tons and 207.7 metres long. Her armament included 8 inch guns and had taken part in the devastating blow to the Royal Navy and British morale that was the sinking of HMS Hood on 24 May 1941. She had a compliment of 42 officers and 1,340 enlisted sailors.

Prinz Eugen

Brest Harbour

With little in the way of ports available directly to Germany, Brest was one of the major ports used by the German Navy as part of the then occupied France. Its location did provide some protection and also included a large U-boat base for attacks as part of the Battle of the Atlantic.

The location, however, also meant that it was easily reached by RAF heavy and medium bombers, so it was easily attacked. All three ships would suffer frequent damage and lost many crew. By February 1941, Adolf Hitler decided that the ships needed to return to their base at and around Wilhelmshaven in Northern Germany. He thought that the allies would be likely to invade Norway and also intended them to attack the convoys supplying the Russians.

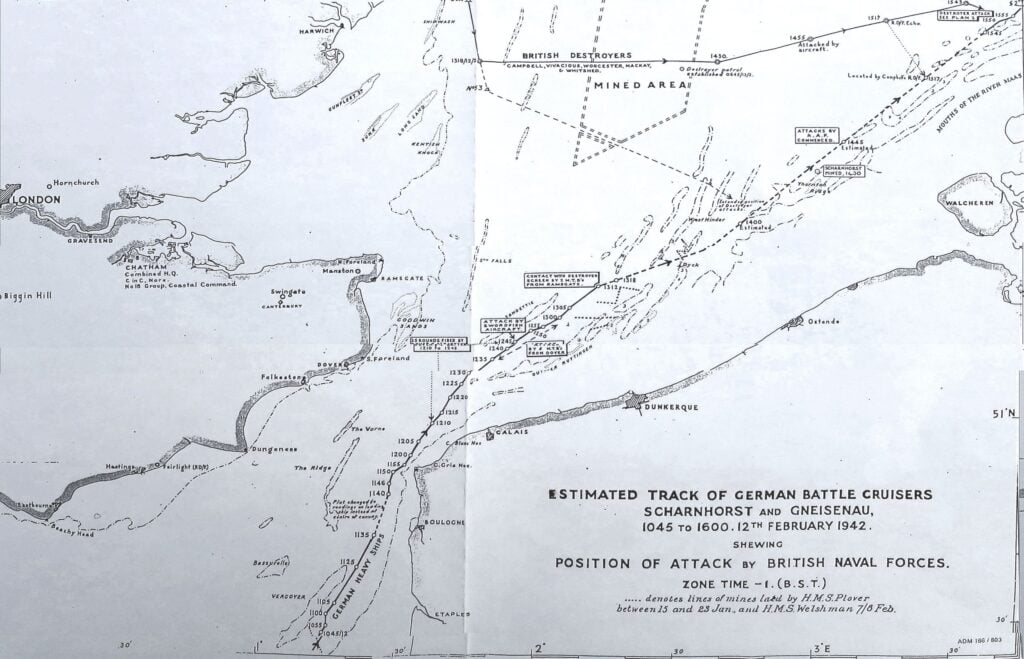

It was decided to take the shorter route through the English Channel instead of the much longer route around the British Isles to benefit from surprise and allow the Luftwaffe to provide air cover. Preparations were made to take the best route, avoiding British minefields, with minesweepers also clearing channels. Air cover was to be provided by the Luftwaffe under the command of Adolf Galland, with six destroyers and later E-Boats then further craft at Cap Gris-Nez. Included as part of these plans for Operation Cerberus, false rumours were spread of a departure for tropical areas, as there was no hiding the fact that the ships were being prepared for departure.

Vertical aerial photograph taken during a daylight attack on German warships docked at Brest, France. Two Handley Page Halifaxes of No. 35 Squadron RAF fly towards the dry docks in which the battlecruisers SCHARNHORST and GNEISENAU are berthed (right), and over which a smoke screen is rapidly spreading. © IWM (C 4109). The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau are shown on the left side of the photo, with the Prinz Eugen moored towards the top right.

Operation Fuller

Operation Fuller had been devised back in April 1941 as a plan for combined operations between the Royal Navy and the RAF. It was a plan to attack ships stationed at Brest should they try and travel up the English Channel. The British were confident that with radar and air patrols, any dash up the Channel could be easily discovered. The Operation would combine the 32 Motor Torpedo Boats (MTB) based at Dover and Ramsgate that would attack with a Motor Gun Boat (MGB) escort from 3,700 metres. Following up would be Swordfish torpedo bombers with fighter escort, plus Beaufort torpedo bombers and the coastal guns at Dover whilst the ships were in range. Bomber command would then attack any damaged ship that had been slowed or stopped.

Once out of the Dover Strait, six Royal Navy destroyers would make torpedo attacks and the RAF would continue to bomb and lay mines in the fleet’s path.

As part of the preparations, the six operational Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers from 825 Squadron Fleet Air Arm under the control of Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde were moved from Lee-on-Solent to RAF Manston in the morning of 4 February 1942.

After the success of the Engima code breaking, decoding of German messages told the British that Vice-Admiral Ciliax had joined Scharnhorst on the 5 February. That and the recent exercises made the Admiralty realise that a departure was imminent. On 8 February reconnaissance showed the battleships were still in dock but another two destroyers had arrived. Decoded messages using Enigma were also reporting that the Germans were minesweeping a route up the Channel.

The Dash Begins – 11 February 1942

The Swordfish of 825 Fleet Air Arm Sqn were stood down from their 5 minute standby as there appeared to be no real threat. Lt Cmdr Esmonde also had an appointment in London to receive his Distinguished Service Order (DSO) from HM King George VI at Buckingham Palace for his part in the attack on the German battleship Bismark some seven months earlier. Others in the squadron took the opportunity to visit family. In the evening some RAF Officers and the FAA crews arranged a small party to celebrate the award with Lt Cmdr Esmonde. The party ended reasonably early with the crews sober enough knowing they would be on duty again early the next day.

Officers and ratings who were decorated for the part they played in the sinking of the BISMARCK, in front of a Fairey Swordfish aircraft. Left to right: Lieutenant P D Gick, RN, awarded DSC; Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde, RN, awarded DSO; Sub Lieutenant V K Norfolk, RN, awarded DSC; A/PO Air L D Sayer awarded DSM; A/Ldg Air A L Johnson, awarded DSM. © IWM (A 5826)

1200 hrs: Vice-Admiral Ciliax, the German commander orders the battle fleet to prepare for departure at 19:30hrs.

The Royal Navy submarine, HMS Sealion, stationed close to the port to monitor the ships, moves away so that she could surface and recharge her batteries. By doing so, those on board lost sight of the port. HMS Sealion was the only modern Royal Navy submarine that was in home waters.

1915 hrs: An RAF Lockheed Hudson from No.224 Sqn takes off from its base at St. Eval in Cornwall for a reconnaissance patrol, flown by Pilot Officer Wilson, but they spot a German night fighter. As a result they turn off all their lights and radar as they approach their target of Brest. After the night fighter is lost, they find they cannot turn their radar back on, so return to St. Eval for a replacement plane.

1930 hrs: The RAF begins its nightly bombing raid at the port, just as the three battleships are casting off. They are ordered back to their berths until the bombers have left.

2115 hrs: After the air raid, reconnaissance photos show the fleet still in harbour, but the fleet is casting off. The replacement RAF aircraft from St. Eval is delayed due to engine problems, so the ships move out unobserved. A British agent in Brest was unable to signal the departure because of the jamming of wireless signals by the Germans.

Midnight: The fleet prepares to enter the English Channel, expecting to reach it by 01:25hrs the next day.

The Dover Straits – 12 February 1942

0400 hrs: 825 Squadron are brought to routine alert, standing by their aircraft ready for take-off at a time before dawn that the Admiralty believed the Germans would use to slip through the straits.

0835 hrs: As dawn breaks, the high alert of the British forces is cancelled by Admiral Ramsey. He was unaware that at this time, the fleet was passing Cherbourg.

825 Squadron are stood down again on what was a cold crisp morning, with freezing snow swirling over Manston. In the corner of the dispersal area, the six obsolete biplanes stood, fully exposed to the elements. Esmonde continues with crew training during the morning, oblivious that their target is making its way up the Channel.

1000 hrs: Sub Lt Brian Rose takes off from Manston on a practice torpedo run in Pegwell Bay.

1016 hrs: British radar finally confirms a large fleet of vessels and aircraft support in the English Channel. Due to the reduced alert, the report was to only slowly makes its way to Royal Navy headquarters and the fleet continued its dash.

THE CHANNEL DASH by Robert Taylor © The Military Gallery www.militarygallery.com (used with permission)

1030 hrs: Two pairs of Spitfires take off, 10 minutes apart. The first pair are from RAF Hawkinge with Squadron Leader Oxspring and Sergeant Beaumont, the second from RAF Kenley with Group Captain Beamish and Squadron Leader Boyd. Both find the fleet, however radio silence as part of Operation Fuller means that they have to wait to report the sightings back at base.

The pair from RAF Kenley spot two Messerschmitt Bf109s and attack them, finding themselves over a German flotilla of two big ships, a destroyer screen and an outer ring of E-boats. After being dived on by around 12 German fighters and attacked by anti-aircraft fire from the ships, they returned flying just above the waves.

The Hawkinge pair report at 10:50hrs and Kenley at 11:11hrs. It isn’t until the Kenley report is received that Admiral Ramsey at Dover is informed. It seems at this point that the full extent of the fleet wasn’t seen due to the poor visibility.

1127 hrs: Bomber Command is alerted to be ready, but although Air Marshall Richard Peirse had about 250 aircraft, the 100 bombers on two hours’ notice were loaded with semi-armour-piercing bombs which were only effective when dropped from 2,100 metres or higher; the poor visibility would make those useless. He therefore orders general purpose bombs to be loaded which would only cause superficial damage but might distract the fleet whilst Coastal Command and the Navy made their attacks.

None of the bomber squadrons could attack before 1500 hours so the main hope was the slender force of Beaufort torpedo-bombers on 42, 86 and 217 Squadrons and the Fleet Air Arm Swordfish of 815 Squadron commanded by Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde. At 1130 hours very few of these aircraft were within range of the German ships. 86 and part of 217 were at St. Eval, in Cornwall; the remainder of 217 was at Thorney Island, near Portsmouth; and 42 was just coming in to land at Coltishall, the fighter airfield near Norwich, after flying down from Leuchars, having been delayed by snow on airfields. Only the six Swordfish at Manston and the seven Beauforts at Thorney Island were in a position to attack within the next two hours.

1155 hrs: The five operational MTBs (44, 45, 48, 219 and 221) at Dover harbour leave to attack the fleet led by Lieutenant-Commander Pumphrey.

1219 hrs: The South Foreland Battery of four 9.2 inch guns at Dover, open fire. They were the only battery that had any means of targeting the warships due to their radar control. Visibility was still poor and there would be no way for observers to see where their shots land. The gunners hoped that the shell splashes would be detected by their K-type radar to allow them to correct, but that had never been tried before. Radar did show the zig-zagging path of the ships, but nothing for where the shells were landing. The Battery fired 33 rounds at the ships but with the ships moving at 35mph and sources stating that the fleet had already passed Dover by the time they opened up. Afterwards, the battery estimated it had made four hits, but in reality the shots had literally missed by a mile. The guns ceased fire when light naval forces and the torpedo-bombers began to attack, but by 1321 hrs the ships had passed beyond the range of the radar, but the barrage continued until 1236 hrs.

Swordfish Preparation and MTB Attacks

When the dash of the German fleet had been put beyond doubt, Admiral Ramsey came to realise that the old Swordfish aircraft were the only aircraft that was immediately available to attack. Torpedo carrying Beaufort aircraft were still in transit to Kent and it would be some time before they could be launched into the attack. Swordfish had previously been considered as it was thought the fleet would have to be attacked during the night. He must have known that to send these aircraft out against the fighter escort and might of the fire from the fleet, it would be a suicidal mission. Admiral Ramsay telephoned the First Sea Lord, Sir Dudley Pound and pleaded with him not to be asked to send the 18 men to what he considered would be their deaths.

The response was a cold reality of war: “The navy will attack the enemy whenever and wherever he is to be found”.

The desirability of holding up the Swordfish until they could be joined by the first echelon of Beauforts from Thorney Island and so launch a co-ordinated attack was discussed between the Air Staff Officer to ViceAdmiral, Dover, and No.16 Group, Coastal Command. For a variety of reasons, but particularly because of the slow speed of the Swordfish and the importance of launching an early attack, it was decided that this delay could not be accepted and that the Swordfish attacks should be launched at the earliest possible moment. It was accordingly arranged that the squadron should be airborne at 1220 and carry out their attack at approximately 1245.

Board of Enquiry 2 March 1942, 825 Squadron’s attack

On Admiral’s Walk in Dover Castle, Vice Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay, who commands the naval forces at Dover, turns his telescope on the French Coast and like many other sailors, he can see without being compelled to close his left eye. He was largely responsible for the successful withdrawal of the BEF from Dunkirk. © IWM (HU 90020)

Back at Manston, Lt Cdr Esmonde readied his crews. They all knew the importance of fighter cover. He was told by 11 Fighter Group that the Biggin Hill Wing of 3 squadrons would provide top cover against the Luftwaffe, with the Hornchurch wing of 2 squadrons providing close cover. They were to rendezvous over Manston and he was asked to confirm the time, to which he replied “Tell them to be here by 1225 hrs. Get the fighters to us on time – for the love of God”.

The necessity for strong fighter protection for the torpedo aircraft was fully appreciated, and, as soon as the presence of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau was definitely known, arrangements were made with No.11 (Fighter) Group for the support of five fighter squadrons. Of these five squadrons, three (the Biggin Hill Wing) were to provide top cover and two (the Hornchurch Wing) were to accompany the Swordfish to deal with enemy flak ships.

Board of Enquiry 2 March 1942, 825 Squadron’s attack

At the command at Dover Castle, Wing Commander Constable-Roberts telephoned Esmonde to stress the Swordfish should only go if he was convinced that he had sufficient fighter cover. He left the final decision down to Esmonde but his mind was already made up and told the Wing Commander to let the Admiral know the squadron would go in. It was felt that even with heavy cover, few Swordfish crews would return from a daylight mission such as this.

1218 hrs: Ten Spitfires of No.72 Squadron, commanded by Squadron Leader Brian Kingcome take off from Gravesend and head towards Manston.

Wing Commander C B F Kingcome © IWM (CH 3553)

1220 hrs: The six Fairey Swordfish torpedo-bombers of 825 Squadron Fleet Air Arm, take off from RAF Manston. The Commanding Officer of RAF Manston, Wing Commander Tom Gleave stands alone in the middle of the snow covered airfield, giving a farewell salute whilst the aircraft went on to circle the airfield waiting for their fighter escort.

1223 hrs: The MTBs from Dover spot the German warships, but their fighter cover hasn’t been airborne in time to reach them. One MTB has engine trouble, the rest have their approach blocked by twelve German E-boats in two lines. The faulty MTB fires torpedoes at the extreme range of 3.7km before returning to Dover, but the rest failed to get much closer, torpedoing between the lines of E-boats. One mistakenly claims a hit on Prinz Eugen. Two Motor Gun Boats (41 and 43) from Dover arrive in time to defend the last MTB from a German class destroyer after their crews had been absent in Dover.

1225 hrs: Three MTBs (18, 32 and 71) leave Ramsgate, under the command of Lieutenant Long, but approach too far astern of the German fleet and are unable to get into a position to attack before the deteriorating weather and engine problems force them back.

A portrait of MTB 32, as she crashes through the waves of the English Channel. © IWM (D 12524)

The rendezvous was fixed for Manston at 1225. This gave the fighter squadrons very little time for briefing, take-off and flight to Manston, and, owing to unforeseen delays, it soon became apparent that the squadrons could not get to the rendezvous in time. The Controller at Hornchurch accordingly rang up Manston and spoke to the Leader of the Swordfish, whom he informed that some or all of the fighter squadrons would be late at Manston. Lieutenant Commander Esmonde decided that he could not delay his departure. The first of the fighter squadrons arrived at Manston at 1228, and on its appearance the Swordfish immediately set course for the target.

Board of Enquiry 2 March 1942, 825 Squadron’s attack

1229 hrs: The Swordfish still circle over the coast off Ramsgate, waiting for the fighter escort that should have arrived five minutes earlier. The weather is closing in.

1230 hrs: Four Hurricanes from No.607 Squadron AuxAF. piloted by F/O. Lane, P/O. Cribbs, F/S. Walker and Sgt. Paul took off from Manston to attack the German convoy. The ships were reported to be off Le Touquet but the aircraft were vectored too far south and only small flak ships were seen. One of these was damaged and set on fire, F/Sgt. Edward Preston Walker (997639) in Hurricane IIB BE476 was seen to secure a direct hit on this ship but he did not return to base. He is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

1232 hrs: The Spitfires of No.72 squadron find the Swordfish. Both sets of aircraft circle for a further two minutes but no further aircraft arrive.

1234 hrs: Esmonde, knowing that it was a case of ‘now or never’, waves his hand and dives down to 50 feet above the sea to lead his squadron out to sea.

Sqn Ldr Kingcombe with the Spitfires is unaware of the real mission, due to the information blackout. His orders are to escort the Swordfish and intervene between German E-boats and British MTBs, which he thought was odd for such a small skirmish.

1236 hrs: The escorts from No.124 Squadron and No.401 Squadron from Biggin Hill both arrive late for the rendezvous. Squadron Leader Duke-Wooley with No.124 squadron knew they would be late, so crosses the coast at Deal, six miles south of Manston to try and catch the Swordfish up. With no sign of them, they carry on north-east and soon become involved with enemy fighters, changing the mission entirely.

The two squadrons from Hornchurch Wing, tasked with attacking the German ships to suppress the anti-aircraft fire arrive five minutes late, so they cross the coast and head out to look for the enemy. However they move too far to the west and are unable to find the ships. They are then attacked by Luftwaffe fighters and get caught up in aerial dogfights.

The remaining two squadrons of the Biggin Hill Wing, although they missed their rendezvous at Manston, proceeded to the target, and were in the vicinity of the German battle cruisers at the time of the Swordfish attack. They were immediately engaged with enemy fighters, of which they destroyed two. Although their presence was unknown to the Swordfish, they thus contributed to the best of their ability to their protection. One Spitfire was lost.

The Hornchurch Wing, which also missed the Swordfish at Manston, proceeded to search for them off Calais, but without success. After patrolling for some time between Calais and Mardyk, they returned to their base.

Board of Enquiry 2 March 1942, 825 Squadron’s attack

The Swordfish Attack

1240 hrs: The Spitfires of No.72 Squadron spot the German ships and are attacked by the fleet’s escort of Bf 109s and Fw 190s, losing contact with the Swordfish. Twenty or more German aircraft circle to make a mass dive on the Swordfish, but three of the Spitfires attack and scatter them.

All ten Spitfires engage with the Luftwaffe aircraft, fighting furiously, whilst the Swordfish pilots sight the battle fleet.

The first section of three Swordfish, led by Esmonde presses on past the screen of the destroyers.

At approximately 1230 the Swordfish, accompanied by 10 Spitfires, left for the target, which was estimated to be some 10 miles north of Calais. They flew in two flights of three, the first in line astern, the second in Vic formation. Some 10 miles from Ramsgate enemy fighters appeared and were immediately engaged by Spitfires. The task of escorting the 80-m.p.h. Swordfish with Spitfires flying at 250 m.p.h. proved a difficult one. The Spitfires, when engaging the enemy were necessarily manoeuvring over a wide area, and the effective camouflage of the Swordfish, combined with the poor visibility, made it hard for the Spitfires to pick them up again once they had lost contact. Although the Spitfires engaged the enemy vigorously and inflicted a number of casualties, it is clear that all the Swordfish were heavily attacked by fighters before they reached the enemy ships.

Board of Enquiry 2 March 1942, 825 Squadron’s attack

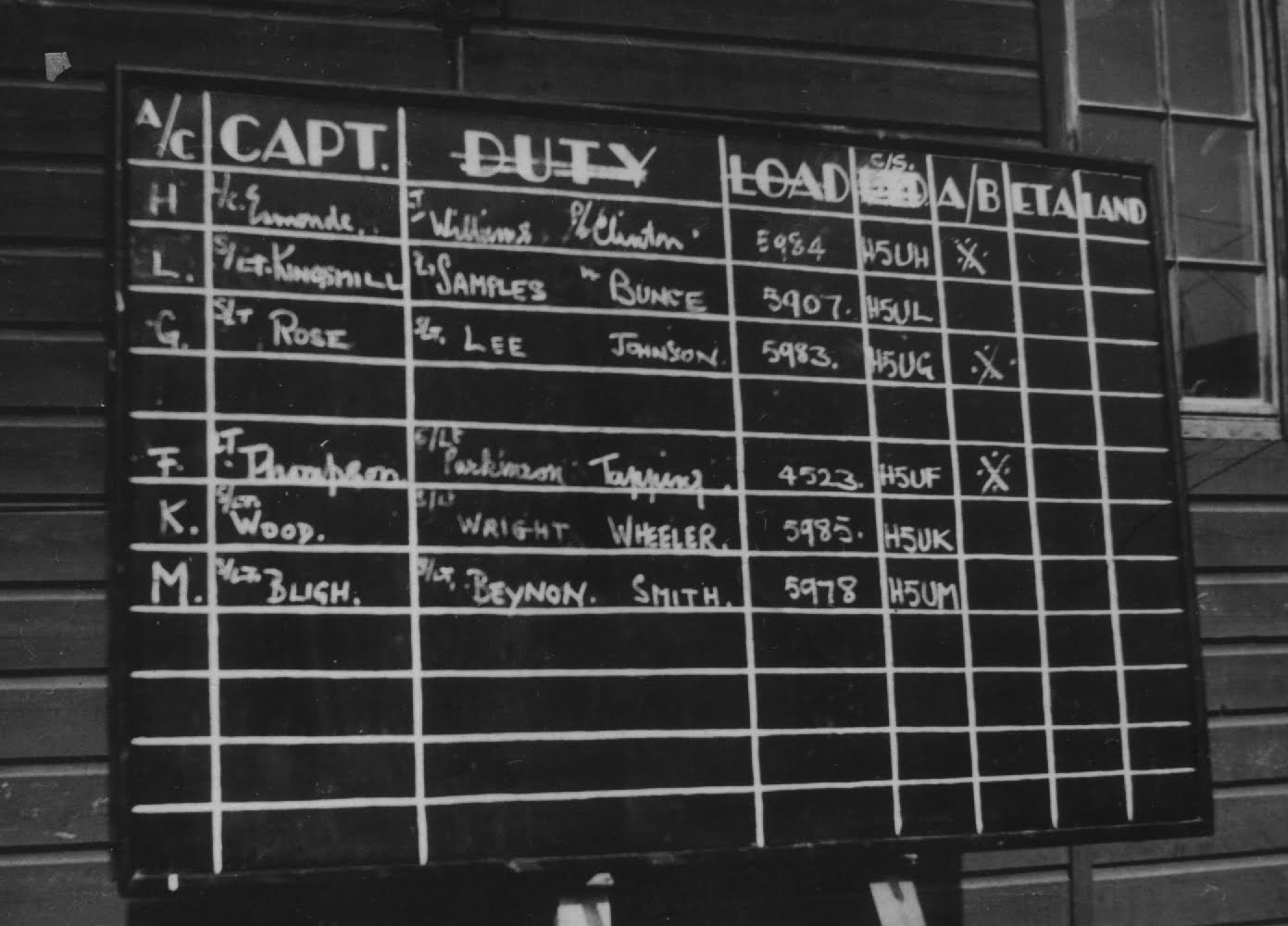

Swordfish W 5984: Lt Cdr (A) Eugene Esmonde (Pilot), Lt William Henry Williams (Navigator), Petty Officer William John ‘Jack’ Clinton (Telegraphist/Air Gunner).

Swordfish W 5983: Sub Lt Brian Rose, Sub Lt Edgar Lee, Leading Airman Ambrose Laurence Johnson DSM (Telegraphist Air Gunner).

Swordfish W 5907: Sub Lt Pat Kingsmill, Sub Lt Reginald McCartney ‘Mac’ Samples, Leading Airman Don Bunce.

Expecting the greatest danger of all to their ships, a suicide attack, the German ships spot aircraft attacking at sea level. When they are 2,000 yards away, every flak gun in the fleet opens up on the slow aircraft. In the rear of Esmonde’s aircraft, P/O Clinton fires his machine gun at the diving Luftwaffe planes that had now joined the attack. Gold tracer shells and flak bursting all around them, cannon shells from the enemy aircraft rips large holes in the fuselage and wing fabric.

One of the Spitfire pilots, F/L Michael Crombie is shocked to see P/O Clinton climb out of his cockpit and crawl along the back of the fuselage to the tail where he beats out flames on his aircraft with is hands.

Once past the destroyers, the 11 inch guns of the battleships open up, creating smoke and flame whilst throwing spray into the aircraft. One shell bursts in front of Esmonde’s aircraft and it destroys the lower port wing. The shuddering aircraft dips, but Esmonde keeps it flying, whilst being badly wounded from wounds in his head and back, aiming for the Prinz Eugen. By this time, P/O Clinton and the Observer Lt Williams are dead from the last attack by a Fw 190.

In a last desperate effort, he raises the Swordfish’s nose and releases his torpedo just before receiving a direct hit, which blows the Swordfish to pieces. Spotting the torpedo, the Prinz Eugen turns easily to avoid it.

The aircraft behind Esmonde was piloted by Sub Lt Brian Rose. When the observer Sub Lt Edgar Lee, who had seen Esmonde crash into the sea, gets a clear sight of the ships, he instructs the pilot to fire, unaware that the speaking tube has been severed. Rose, wounded in the back by cannon shell splinters, holds onto the controls. The same cannon fire kills the rear gunner Leading Airman ‘Ginger’ Johnson. Rose releases their torpedo towards the Gneisenau but they have been hit in their main petrol tank, which doesn’t catch fire but deprives the engine of fuel. Rose switches to the emergency fuel tank and manages to bring the plane down half a mile from the Prinz Eugen. Lee manages to get Rose out of the aircraft and into the dingy, just as the Swordfish sinks, taking Johnson’s body down with it.

The two survivors wait until the German ships have moved off before firing two distress signals from their Verey light pistol, and are picked up by an MTB after 1½ hours.

“Channel Dash Heroes” – by Philip E. West – Reproduced with permission from SWA Fine Art Publishers

The Straits of Dover, 12th February 1942. Sub Lieutenant Edgar Lee helps his badly wounded pilot, Sub Lieutenant Brian Rose from the cockpit of their downed Swordfish, before it sinks into the depths of the English Channel following their brave attack on the mighty German fleet.

The third aircraft flown by Sub Lt Pat Kingsmill, sees Leading Airman ‘Don’ Bunce get credited with shooting down a German fighter. One cannon shell hits their aircraft immediately behind the pilot and explodes, wounding both Kingsmill and the observer ‘Mac’ Samples. Failing to line up the first time, the pilot turns for a second run through the intense flak. Whilst Samples is wounded again, their torpedo is released from about 2,000 yards. Heading back over the screen of destroyers, a shell damages the engine, reducing its power. Unable to maintain height, the engine bursts into flames and the port wing catches fire, so they head for the British MTBs whilst watching the second set of three Swordfish, led by Lt J C Thompson, head towards the Prinz Eugen.

The three remaining Swordfish, maintain a steady course, but are blown to pieces by the exploding shells. Of the nine crew, only the body of Leading Airman William Granville Smith is recovered.

Swordfish V 4523: Lt (A) John Chute Thompson, Sub Lt (A) Robert Laurens Parkinson, Leading Airman Ernest Tapping.

Swordfish W 5985: Sub Lt (A) Cecil Ralph Wood, Sub Lt (A) Eric Herbert Fuller Wright, Leading Airman Henry Wheeler.

Swordfish W 5978: Sub Lt (A) Peter Bligh, Sub Lt (A) William Beynon, Leading Airman William Grenville Smith

None of the Swordfish’s torpedoes found their targets.

The operations board of 825 Fleet Air Arm Squadron after it had been written up with details of the six Swordfish torpedo biplanes that were sent against the German fleet. From the album of WT Page, 174 Squadron, courtesy of the Battle of Britain London Monument.

Amongst the five survivors of the Swordish attack, only Edgar Lee was not wounded. Bunce was slightly wounded, Kingsmill and Samples had serious leg injuries and Rose had back injuries. He would die in his aircraft two years later.

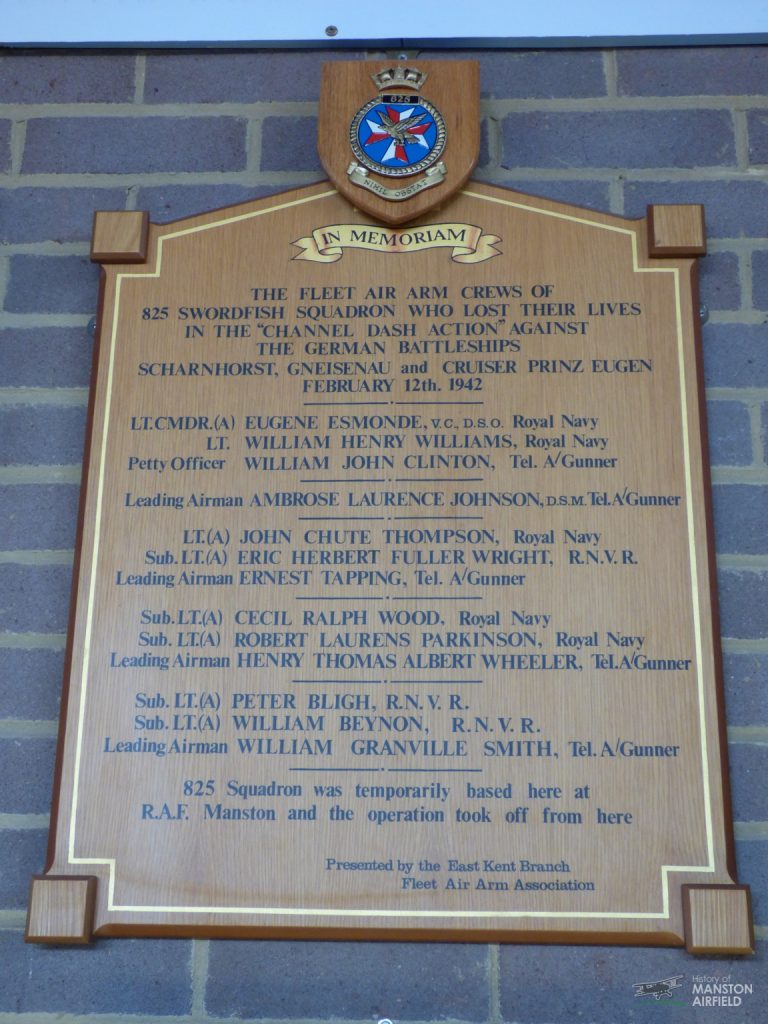

Surviving Officers were each made a companion of the DSO and Bunce received a CGM. Lt Cdr Eugene Esmond DSO received a posthumous Victoria Cross. The twelve others who lost their lives received posthumous Mentions in Dispatches. Had they survived there is little doubt that they would all have been similarly decorated for gallantry in the face of the enemy, however, a posthumous Mention in Despatches is the only recognition for bravery that can be given after death, other than the Victoria Cross.

The body of Lt Williams was recovered from the sea, taken to RAF Manston and buried in Aylesham Cemetery, near Dover, Kent. The body of PO Clinton also recovered from the sea was returned to his home in Ruislip, Middlesex, where he was buried with full military honours in St Martin’s Church Cemetery. Lt Cdr Esmonde’s body was recovered from the River Medway at Gillingham, Kent, having drifted from near Calais. He was buried on 30th April 1942 in grave number 187 of the RC Section, Naval Reservation, Woodland Cemetary, Gillingham, Kent, with full military honours. Nearly two weeks later, the body of Leading Airman W G Smith was found on Upchurch Marshes, close to Gillingham, Kent. Naval authorities would not allow his widow to have his body for burial at his home town of Poplar, East London, and he was buried at a private ceremony in grave number 1393 in the same Woodlands Cemetery Naval Reservation, 40 yards away from his Commanding Officer.

Lt Cdr Eugene Esmond’s Victoria Cross Citation

The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the grant of the VICTORIA CROSS, for valour and resolution in action against the Enemy, To:

The late Lieutenant-Commander (A) Eugene Esmonde, D.S.O., Royal Navy.

On the morning of Thursday, 12th February, 1942, Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde, in command of a Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm, was told that the German Battle-Cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the Cruiser Prinz Eugen, strongly escorted by some thirty surface craft, were entering the Straits of Dover, and that his Squadron must attack before they reached the sand-banks North East of Calais. Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde knew well that his enterprise was desperate. Soon after noon he and his squadron of six Swordfish set course for the Enemy, and after ten minutes flight were attacked by a strong force of Enemy fighters. Touch was lost with his fighter escort; and in the action which followed all his aircraft were damaged. He flew on, cool and resolute, serenely challenging hopeless odds, to encounter the deadly fire of the Battle-Cruisers and their Escort, which shattered the port wing of his aircraft. Undismayed, he led his Squadron on, straight through this inferno of fire, in steady flight towards their target. Almost at once he was shot down; but his Squadron went on to launch a gallant attack, in which at least one torpedo is believed to have struck the German Battle-Cruisers, and from which not one of the six aircraft returned. His high courage and splendid resolution will live in the traditions of the Royal Navy, and remain for many generations a fine and stirring memory.

Distinguished Service Order Awards

The Conspicuous Gallantry Medal.

Naval Airman First Class Donald Arthur Bunce, FAA/SFX.63I,

who was Air Gunner in the Swordfish aircraft piloted by Sub-Lieutenant Kingsmill. With his machine on fire, and the engine failing, he stayed steadfast at his gun, engaging the Enemy fighters which beset his aircraft. He is believed to have shot one of them down. Throughou tthe action his coolness was unshaken.

Mention in Despatches (Posthumous).

The Funeral of Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde, on 30 April 1942 at the Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham (British Pathé)

The Fleet move towards the North Sea

1312 hrs: By this time the last vain attempt by the MTB from Ramsgate has failed. The Navy launches its destroyers from Harwich and the RAF bombers make ready to attack the fleet in the North Sea.

1330 to 1334 hrs: Four Bristol Beauforts of No.217 Squadron from Thorney Island (West Sussex) take off from the seven available there. Among the other three were two armed with bombs which would need changing to torpedoes and one with a technical fault although the Squadron records show that three would later take off. The four were twenty minutes late to their planned rendezvous with their fighter cover at Manston. To make up for this delay both sets of aircraft were ordered while in the air to proceed independently to the targets but because of radio frequency problems the torpedo bombers did not receive the message. Eventually the front section of two Beauforts set off for the French coast, found nothing and returned to Manston, where they discovered for the first time the nature of their target. Meanwhile the two rear Beauforts, which had lost touch with their leaders, had already landed at Manston, learned their target and the latest position of the ships and set off towards the Belgian coast.

1420 hrs: The first wave of 73 RAF bombers take off. Most of them managed to reach the target area, individually or in pairs, between 1455 and 1558, but in the thick low clouds and intermittent rainstorms only ten crews saw the German ships long enough to release their bombs.

1420 hrs: Eight further Hurricanes from No.607 Squadron AuxAF took off from Manston to attack the escort ships flown by S/Ldr. Mowat, P/O. MacDonald, P/O. Doudy, W/O. Rupert John Ommaney, P/O. Ernest John Staerck (recorded as Staeveck), W/O. Dutuacky, F/Sgt. Noel McClean (recorded as McLean) and F/Sgt. Gill. One tanker was destroyed by S/L. Mowat, P/O. Doudy and P/O. MacDonald and another tanker damaged. F/Sgt. Gill and F/Sgt. McLean damaged an Bf109 which got in the way. P/O. Staerck and W/O. Ommaney in Hurricane BE222 did not return according to the Squadron records, but it appears that F/Sgt. McLean in Hurricane BE670 also did not return. Those lost are commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

1425 hrs: Nine Beauforts from No.42 Squadron take off from Coltishall. They had flown in from Lauchars with five other Beauforts, but found no facilities for torpedo bombers, so only those that had flown from Coltishall already armed with torpedoes too off again, heading south to Manston to link up with fighters and some Hudsons intended for diversionary bombing. When the Beauforts arrived over Manston they were unable to form up with the other aircraft. After orbiting for half an hour, in a eerie mirror of the earlier events, the commander decided to set a course based on information of the enemy’s position given before they had left Coltishall. Six Hudsons followed him, the remainder continued to circle until almost 1600 hrs before withdrawing to Bircham Newton.

Time TBC: In thick cloud and heavy rain the nine Beauforts of No.42 Squadron and six Hudsons pressed on towards the Dutch coast, but the two formations quickly lost touch. After an ASV contact (air to surface radar), the Hudsons sighted the enemy and attacked through heavy flak. Two Hudsons were shot down and no damage was done to the convoy. A few minutes later, six of the nine Beauforts, flying just above sea-level also came across the Germain force – the other three had already released their torpedoes against what might have been Royal Navy destroyers. Most of the torpedoes were seen to be running, but none found their mark.

1420 to 1430 hrs: Three more Beauforts of No.217 Squadron take off from Thorney Island. Among these was MW-F (AW278) crewed by Pilot F/Lt Arthur John Heneage Finch RAF (39937), Sgt. David Yule Fyffe RAF (749346), Sgt. Thomas McNeil RAF (1355426) and F/Sgt. Albert Henry Leeds Jackson RNZAF (403778). The aircraft along with F/Lt Finch, Sgt. Fyfe and Sgt. McNeil had been involved with the sinking of SS Madrid on 9th December 1941 from Manston. They were pronounced missing, believed killed when their aircraft failed to return.

Another of the three Beauforts (MW-X), crewed by Sgt. Rout, Leaver, Foulkes and Vagg landed after the attack at Manston with Sgt. Rout wounded in the hand by a shell fragment, his Wireless Operator/Air Gunner with a bullet in his arm and leg and his rear gunner wounded in the eye by Perspex splinters and a number of holes in his aeroplane.

Beaufort AW275 (MW-L) crewed by P/O Stewart, P/O Harrison and Sgts. Barnes and Bower were set on by fighters as they went into attack but Sgt Bower fought back with his two G.O.s and Stewart made his attack when he was again set on by fighters. Again Sgt. Bower fought them off, claiming one down and one damaged.

1430 hrs: Beauforts of No.86 and No.217 Squadrons arrive at Thorney Island after being hastily ordered from St. Eval in North Cornwall. After adjusting the torpedoes and refuelling they took off again to link up with fighters over Coltishall.

1432 hrs: The Scharnhorst strikes a mine just off the Dutch coast. Damage is extensive with a large hole in the starboard side and compartments flooded. Vize Admiral Ciliax transfers to a Destroyer, the Z29 and the rest of the fleet steams on, leaving four S-boats to protect the ship.

1437 hrs: The next wave, of 134 RAF bombers, begin to take and arrive in the target area between 1600 and 1706. Twenty of these are known to have delivered attacks.

1500 hrs: The Scharnhorst has been repaired and sails at 27 knots to catch up with the rest of the fleet, escaping before the RAF or Royal Navy have chance to find her. Beauforts of No.86 and No.217 Squadrons from St. Eval reach Coltishall but find no sign of the escort they were expecting, so head out to sea.

1540 hrs: The pilots in the two Beauforts that had taken off from Manston sighted a large warship which they took to be the Prinz Eugen. Despite intense flak they turned in and launched their torpedoes from a thousand yards range but to no avail.

1545 hrs: RAF bombers attack the fleet. Over 240 Beaufort, Manchester and Wellington bombers had been sent to find the fleet. The Manchesters and Wellingtons struggle with the low clouds and fighter escorts and fail to score any hits. The Beauforts struggle to find their targets and are also harassed by German fighters. German ships suffer virtually no damage, but they lose 17 escort planes. The RAF lose 15 bombers, 15 coastal command planes and 17 fighters, with 106 aircrew killed or missing.

1555 hrs: The flotilla of five elderly destroyers engage with the German fleet and the three German battleships return fire.

1600 hrs: HMS Worcester is hit after coming within 400 yards of the Gneisenau and firing her torpedoes at her. The Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen open fire on HMS Worcester and it sustains several hits, killing 27 crew and crippling the ship. She and the rest of the fleet are ordered back to Harwich. RAF bombing continues without success.

1606 to 1609 hrs: One No.217 Squadron Beaufort and three aircraft of No.22 Squadron took off from Thorney Island (TBC). One of the No.22 squadron aircraft piloted by F/L White failed to return.

Beaufort AW.252 (MW-E) crewed by P/O. Etheridge, Sgts. Hutchinson, Clayton and Williamson that left at 1609 hrs had their hydraulic gear shot away and were forced to crash land at Horsham St. Faith using their torpedo as an undercarriage. The rear gunner was injured in this landing, conflicting reports received as to the extent of his injuries, being cleared up about a week later, when informed that he had never been on the seriously ill list.

1615 hrs: A third and final wave of thirty-five RAF bombers take were over the target from 1750 to 1815. Nine managed to attack. All told, 242 aircraft of Bomber Command attempted to find the enemy during the afternoon; and of those that returned, only 39 succeeded in bombing. Fifteen aircraft were lost, mostly from flak and flying into the sea and twenty damaged. No hits were scored on the vessels.

1710 hrs and 1800 hrs: Two Beauforts from No.217 Squadron that had failed to find the ships earlier in the afternoon had set off again from Manston. Operating independently, both picked up the Scharnhorst off the Dutch coast with the aid of their ASV. Their attacks delivered at 1710 and 1800 also proved unsuccessful.

1805 hrs: In the growing dusk with visibility down to less than 1,000 yards and cloud base at 600 feet, the Beauforts of No.86 and No.217 Squadrons from St. Eval came across four enemy mine-sweepers. One pilot caught sight of what he took to be a big ship, but by then his aircraft was so damaged he was unable to release his torpedo.

1810 hrs: As evening falls, the RAF recalls the last of the 242 bomber signalling the failure of Operation Fuller.

1830 hrs: The Beauforts of No.86 and No.217 Squadrons from St. Eval abandon their search and set course back to Coltishall, with two of their number, victims of flak or the flying conditions failed to return.

Time TBC: Australia’s one-legged Beaufighter pilot, Flight Lieutenant Bruce Rose DFC was probably the last airman to see the Scharnhorst that day. Flying through intense flak from the destroyer screen, he completely circled the cruiser before leaving for base. It was almost dark when he left.

Single aircraft of Coastal Command which had been trying to shadow the German formation since about 1600 obtained two sightings before dark and two or three ASV contacts afterwards – the last of them, against the Scharnhorst, as late as 0155 on 13 February. Their reports correctly indicated that the German force had split up, but were too late to be of any value. As a final effort, twelve Hampdens and nine Manchesters were sent to lay mines in the Elbe estuary during the night. Only eight aircraft laid their mines and none of these did any damage.

1955 hrs: The Gneisenau hits a British mine off the Dutch Coast, near Terschelling laid by 5 Group Hampdens or Manchesters during recent nights, but although it creates a large hole in the side of the hull, the ship is repaired and back under way within 30 minutes.

2135 hrs: In the same minefield, the Scharnhorst hits two British mines. Despite taking in thousands of tons of water, total electrical failure and damaged engines, she is back under way by 2215 hrs.

The fleet is safe, for now (13th February 1942)

0630 hrs: The Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen arrive at Brunsbüttel before dawn and wait for daylight to dock.

0800 hrs: Admiral Ciliaz, with the damaged Scharnhorst limping towards Wilhelmshaven, calls Adolf Hitler to declare Operation Cerberus is a success.

0930 hrs: Prinz Eugen and Gneisenau dock at their berths at Brunsbüttel.

1000 hrs: The Scharnhorst finally docks after hitting two mines and being largely unprotected for a day, at her berth in Wilhemshaven.

Reaction

In Germany, those involved with Operation Cerberus were hailed as heroes.

In Britain the press was outraged. An enquiry concluded that everything was done that could be done, but wasn’t published until 1946, even though considered to be a ‘white wash’.

Although they escaped, the German ships were virtually trapped in their Northern bases. They were no longer a threat to the Atlantic conveys and were to be continually bombed.

The Scharnhorst was sunk in the Battle of the North Cape on 26 December 1943 by the Royal Navy with the loss of 1,932 of her crew.

The Gneisenau was damaged by repeated bombing and eventually had the ignominy of having her guns removed and used as coastal defences in Norway. She was eventually sunk on 27 March 1945 in Goteshafen as a blockade to the advancing Russians.

The Prinz Eugen carried out operations in and around Norway until the end of the war and was decommissioned on 7 May 1945. Awarded to the Americans she was used in atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll and sank on 22 December 1946 after developing a leak.

Commemoration

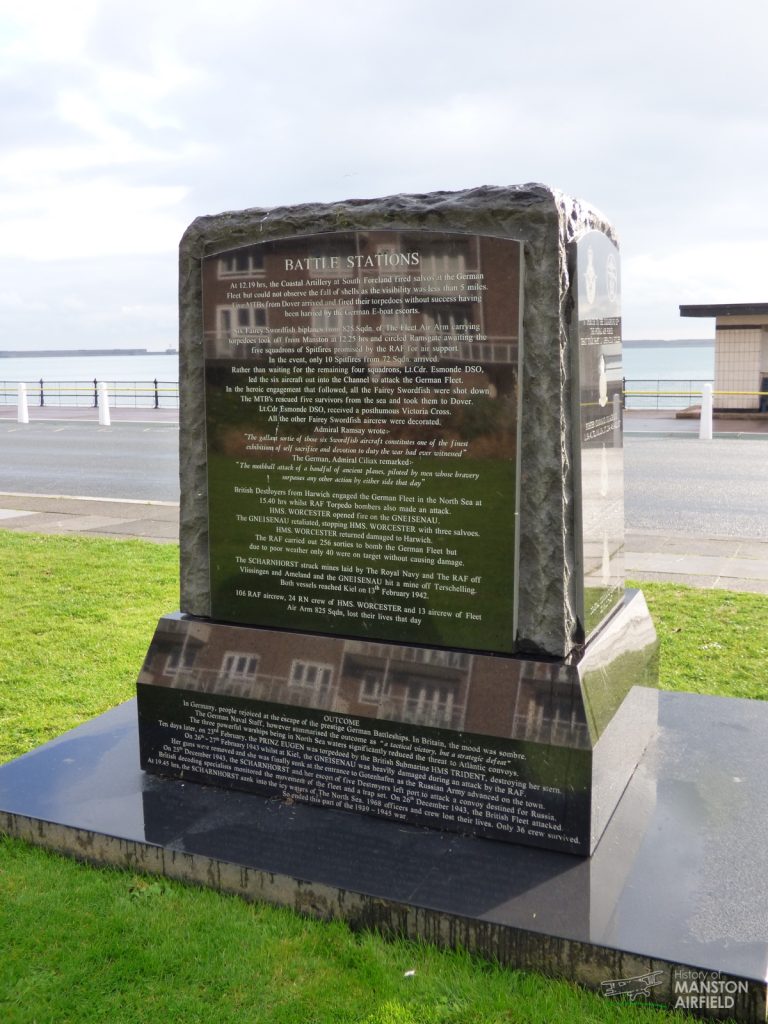

The Channel Dash Association unveiled their memorial monument located at Ramsgate on 12 February 2010. It is the regularly the location for a memorial ceremony on the anniversary of 12 February.

http://www.manstonhistory.org.uk/the-channel-dash-memorial-ramsgate/

There is also a monument to all those that took part in the operations from both sides in Dover.

Dover Memorial

Dover Memorial

Part of the display at the Spitfire and Hurricane Memorial Museum

As any updated or additional information is obtained, we will update this post.

First posted: Feb 12, 2017

Last Updated:

More information:

The Channel Dash Association: Since their closure, their website is archived here

The Channel Dash Association Schools Learning Resource: http://channeldash.org/learning/ (Archived site)

Visit The Spitfire and Hurricane Memorial Museum. for a special display area on The Channel Dash, including transcripts of interviews with Lt Cdr Edgar Lee and Leading Airman Donald Bunce.

Book: Run the Gauntlet – The Channel Dash 1942 by Ken Ford https://www.amazon.co.uk/d/cka/Run-Gauntlet-Channel-Dash-1942-Ken-Ford/1849085706

https://www.scharnhorst-class.dk/scharnhorst/history/scharncerberus.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Channel_Dash

http://www.navweaps.com/index_oob/OOB_WWII_Atlantic/OOB_WWII_Cerberus.htm

https://www.scharnhorst-class.dk/scharnhorst/history/scharncerberus.html

https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2019/03/11/coastal-command-bombers-against-the-german-navy-iv/

Last Updated: